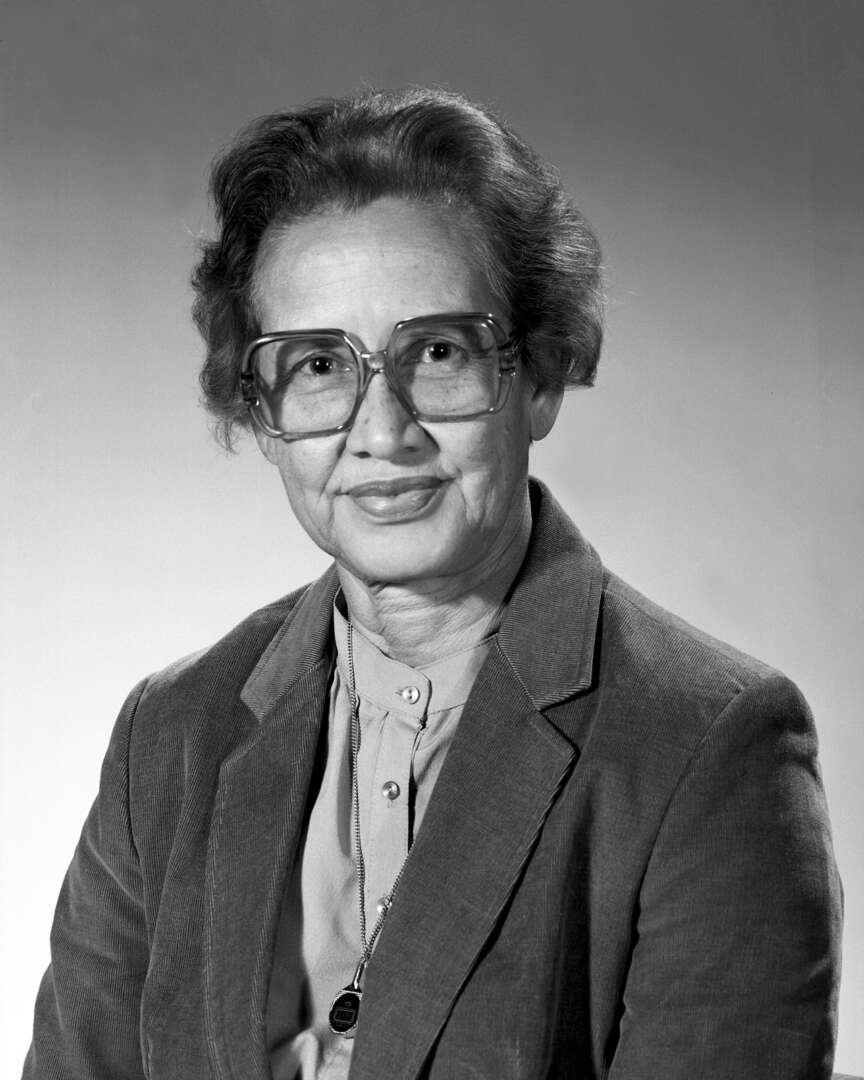

Before computers, there was Katherine Johnson. Her calculations sent astronauts into orbit, guided them to the moon, and brought them safely home. For 33 years, she was one of NASA's "human computers"—a Black woman doing the math that made America's space program possible, even as Jim Crow laws forced her to use separate bathrooms and eat at separate tables.

A Mind Like No Other

Katherine Coleman was born in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, in 1918. Her brilliance was evident from the start—she was so advanced that she began high school at age 10 and graduated from West Virginia State College at just 18, summa cum laude, with degrees in mathematics and French. Her professor, W.W. Schieffelin Claytor, the third African American to earn a PhD in mathematics, created advanced courses just for her.

In 1953, Katherine joined the all-Black West Area Computing section at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the predecessor to NASA. The "computers" were women who performed complex calculations by hand—and Katherine quickly distinguished herself by asking questions no one had asked before.

"I counted everything. I counted the steps to the road, the steps up to church, the number of dishes and silverware I washed... anything that could be counted, I did."

— Katherine JohnsonThe Woman Who Sent America to Space

When NASA began planning America's first manned spaceflight, Katherine was assigned to the Space Task Group. In 1961, she calculated the trajectory for Alan Shepard's Freedom 7 mission—America's first human spaceflight. Her work helped define the path the capsule would travel from launch to splashdown.

But her most famous moment came in 1962, before John Glenn's orbital mission. NASA had begun using electronic computers, but Glenn didn't trust them. Before he would climb into the capsule, he made one request: "Get the girl to check the numbers." Katherine ran the same calculations as the IBM computer by hand. Only when she confirmed the results did Glenn agree to fly.

He orbited the Earth three times and returned safely. America had entered the Space Age—and Katherine Johnson had done the math.

"Get the girl to check the numbers... If she says the numbers are good, I'm ready to go."

— John Glenn, before his historic orbital flightTo the Moon and Beyond

Katherine's most critical work came with the Apollo 11 mission in 1969. She calculated the trajectory that would take Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins to the moon and back. Her calculations helped synchronize the lunar lander with the orbiting command module—a rendezvous in space that had never been attempted.

She later worked on the Space Shuttle program and plans for a mission to Mars. Throughout her career, she co-authored 26 scientific papers—an extraordinary number for someone who had to fight just to be allowed in the room.

Hidden No More

For decades, Katherine Johnson's story remained largely unknown outside NASA. That changed in 2016 with the book and film Hidden Figures, which brought her story—along with those of Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson—to the world. The film earned three Academy Award nominations and introduced a new generation to the Black women who helped win the Space Race.

In 2015, at age 97, Katherine received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. In 2017, NASA dedicated the Katherine G. Johnson Computational Research Facility in her honor. She lived to see herself become an American icon.

Achievements

- Calculated trajectory for America's first human spaceflight (1961)

- Verified computer calculations for John Glenn's orbital mission (1962)

- Calculated trajectory for Apollo 11 moon landing (1969)

- Co-authored 26 scientific research papers

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (2015)

- NASA facility named in her honor (2017)

- Congressional Gold Medal (posthumous, 2019)

- Subject of the film "Hidden Figures" (2016)

Katherine Johnson passed away on February 24, 2020, at the age of 101. She had lived to see her calculations take humans to the moon and her story inspire millions. When asked about her legacy, she was characteristically modest: "I was just doing my job." But her job helped change the course of history—and proved that the brightest minds come in all colors.